We’d love to invite you to the private view of GLORY BOX!

- Seren Seren

- Jun 29, 2025

- 3 min read

When we hear the words 'inherited' or ‘collection’ in the context of art, we often think of wealth, artefacts, or institutional value. For Grace Clifford, Harley Roberts and Kelly Wu, materials are gathered out of necessity, as a means of holding on, filling gaps, or processing experiences that aren’t easily archived. GLORY BOX, questions what it means to inherit and collect, and how that accumulation complicates ideas of value when placed inside a commercial environment.

These are artists who have inherited labour ingrained in their bodies and minds, who have chosen to direct it towards the gallery. For Grace Clifford (b. 2000, Birmingham), who works underneath a factory in Sheffield, it's a legacy of dirt under nails, metal in the blood; a haunting, generational rhythm of factory work. Clifford presents ‘Anthony Caro’s Offcuts’; rusted, layered, sharp-edged fragments of scrap metal from Anthony Caro’s studio given to her during a residency at Yorkshire Sculpture Park. Frustrated with this gift, she held onto the metal like a maternal burden; a weight of someone else’s legacy, reluctantly carried and cared for by Clifford’s hands.

‘Sometimes I feel so drawn to material that it wakes me up at night. I am compelled to seek material by a force I respect deeply and don’t want to explain. I cannot believe it could be me… I think churches and factories are the same thing.’

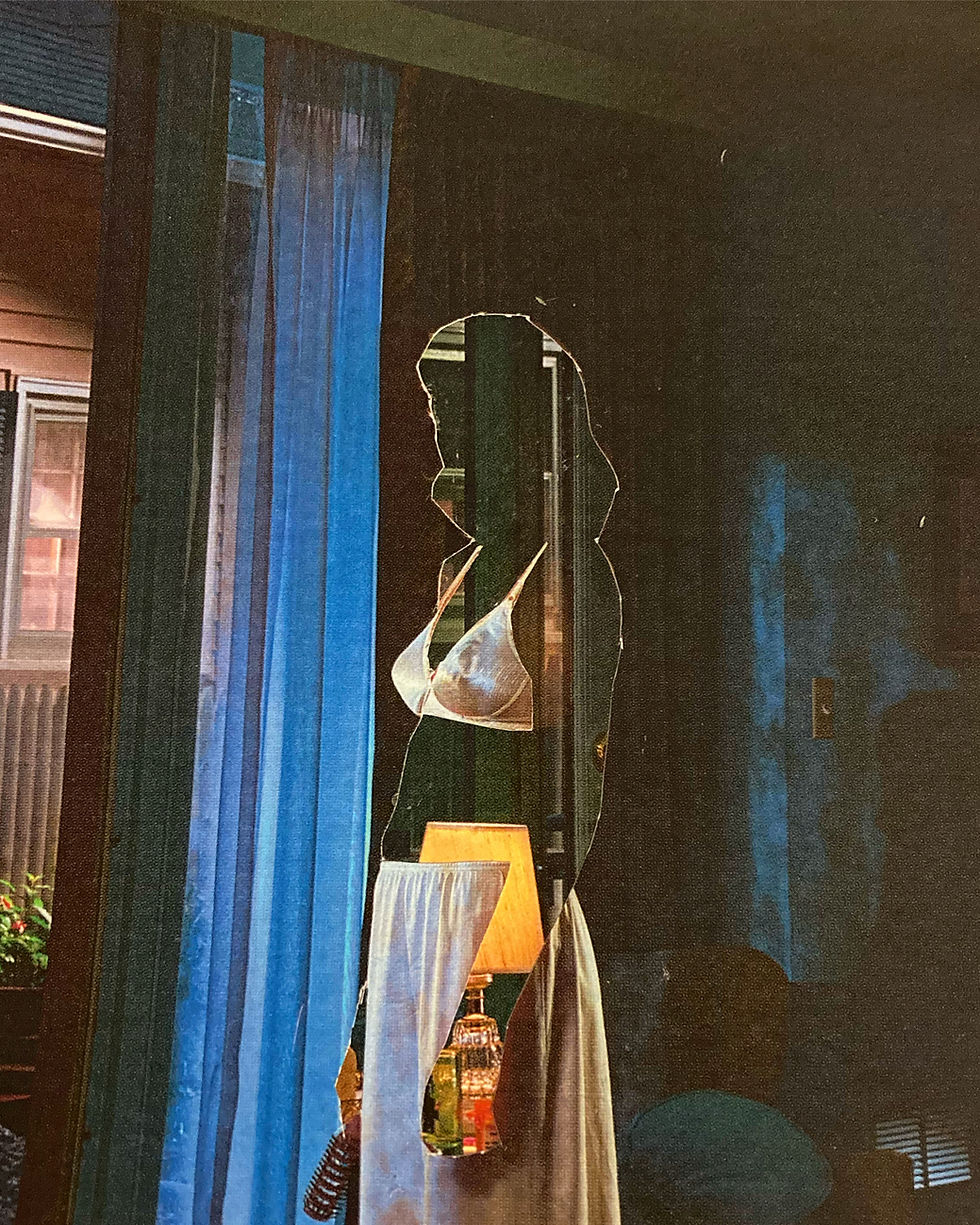

A slow rhythm underpins GLORY BOX, a beat that runs through each artist’s practice as a low-frequency hum. It echoes the seductive loop of the Portishead song the show takes its name from, carrying into the improvisational paintings of Harley Roberts (b. 1995, Grimethorpe). A recent graduate of the Royal College of Art, Roberts describes painting as apparition, a way of haunting whilst still alive. His works drift between figuration, landscape, and abstraction, a patchwork of oil, graphite and canvas with fragments of text and memory. Haunted not by specific figures, but by the social and psychic aftermaths of things left unresolved.

‘A painting should not be pinned down because in actuality there is nothing accurate about it at all, but an improvisation of the things seen and felt.’

Kelly Wu (b. 2001, Chelmsford) presents Palindrome, three identical swords which make up the Essex coat of arms. For Wu, they are a symbol of entrapment, shaped by nine childhood moves across Essex and a recent return to China after 15 years spent in the UK. The swords can be viewed from all angles, circling back on themselves, like how Essex always circles back to Wu. Palindrome discusses tensions around identity, heritage, absence, and desire. Now working in a school, Wu reflects on the performance of assimilation across cultures and institutions. Their language is shaped by repetition, dislocation, and return, often using domestic materials borrowed from their parents’ home. The familiar choreography of packing and unpacking becomes rhythmic.

Earlier work, The State in Which We Are, featured a tower of their mother’s hoarded belongings, brought into the gallery as a gesture toward letting go. This impulse to hold on recurs throughout Wu’s practice, from tattooing the details of their first solo show across their back, to quietly stealing doorstops from galleries and institutions. Describing themselves as ‘a crook’ and a ‘beauty blender,’ Wu blurs souvenirs and shrines, the fragments left behind.

Each artist’s materials come from making do; objects that arrive through circumstance rather than choice. They regard these materials as charged with histories, latent with feeling.

‘Lack of privilege can itself be a privilege because you are left with no illusions and have to create your own with the materials available.’ - Roberts

Clifford recalls hoarding, and hiding bottles she bought during the rise of reusable culture not out of defiance, but guilt and shame. My eternal chalice features used plastic bottles guarding a small angel statue. Lined up in front of a sunlit window and situated higher than the Caro offcuts, the vessels glow with a devotional glory. Clifford, Roberts and Wu have a generational instinct to hide, gather and repurpose.

GLORY BOX is the Working Class Creatives’ first exhibition situated within central London’s commercial gallery scene. Operating on the periphery, the exhibition exists not as part of the main program, but as a storeroom, box bedroom, church, glory hole, factory: perched on the edge of the ‘gallery world’, where working-class survival and labour quietly persist amongst polished spectacle. The title implies thus ‘in all its glory’ but this isn’t a debutante moment. Glory here is complicated. It’s devotional; to grief, to language, to scrap metal and the things we carry in our bodies without intention.

For further enquiries, contact:

Seren Metcalfe workingclasscreativesdatabase@gmail.com

Comments